Chatbots are far from being widely deployed, but have received enough coverage since their introduction that most people are now familiar with the concept. Much like we all became accustomed to interactive voice response (IVR) triaging our phone calls to a company and answering our basic questions, it’s likely we’ll see something similar develop with chatbots on text-based channels like SMS and Facebook Messenger.

But in order for this technology to get off the ground, understanding how humans want to interact with it – and its current limits as to what it can and cannot do – is critical. Suppose you drew a Venn diagram with customer needs on one side and chatbot capabilities on the other. It would be different for every brand, but there would be, inevitably, only partial overlap. It’s incumbent on developers to not build out the features customers don’t need – and on marketing and customer service teams to appropriately communicate to customers that the chatbot will only be capable of responding to a subset of their needs.

A recent piece of research from Mindshare, “Humanity in the Machine”, evaluated how consumers really feel about interacting with these chatbots, and how the user experience with chatbots can deliver positive human experiences. They partnered with IBM Watson for functionality and with Extreme Biometrics to gauge stress levels and sentiment.

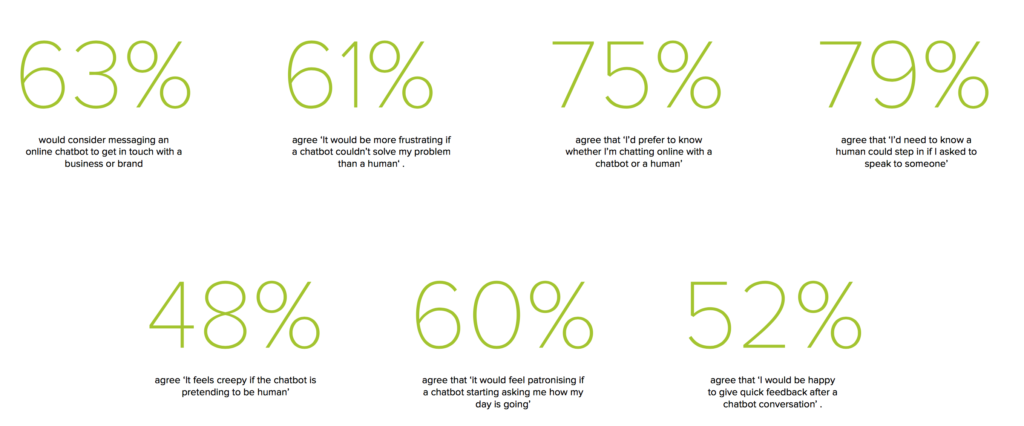

The research found about two-thirds of people willing to engage with a chatbot, as long as the bot didn’t pretend to be human:

A similar percentage of those willing to engage with a bot said they’d be more frustrated if a bot couldn’t help – making setting expectations and defining the role of the bot ever so important.

Much of their research also focuses on good bot design, after the bot’s role is defined. The bot should reflect the brand’s tone of voice, of course, and skip the faux-friendliness (deemed “creepy” by about half). It should focus on trust – not trying to pretend to be something it’s not (a person) and asking supplemental questions so that the customer feels it’s collecting sufficient information. (Interestingly enough, this trust includes leveraging the capability to address sensitive topics of discussion we might rather not discuss with a another human.) It should also be built in a way that it can continuously learn and improve – this can include machine learning as well as taking immediate feedback from customers, many of whom are willing to rate their interactions.

This research should be enlightening for anyone who develops chatbots – it was for me, and led me to make some additions to a recent bot I built for an automotive company – and should also be reassuring to anyone who fears a dehumanizing element to this “robot revolution.” Customers don’t want bots to be human, or to be better than humans – they want a frictionless experience that improves their ability to manage a defined task. It’s incumbent upon developers to understand customer needs and use technology to enable chatbots to assist as best they can – and upon others in the organization to appropriately communicate the bot’s capabilities to customers, whom, it turns out, don’t actually want the bot to be superhuman. And when I phrase it that way, it sounds easy – right? 🙂